Kris:

I love the Dispossessed, it is one of my favourite books. Whilst both can be read independently, this adds extra texture to it.

Whilst it is science fiction as it is positing a revolution on an alien world, really it is a thought piece about the difficulty of social change.

One of the common recurring issues with revolutions is how hard it is for them to not slip into dictatorship. On the one hand, if it fails violent oppressive counter-revolution will follow. On the other hand, if there is not a strong guiding force at the wheel it is hard for things to be pushed forward as intended against entrenched interests.

This is really looking at this from an anarchist’s perspective. And whilst it is clear Le Guin favours anarchy over capitalism here, we explore it with eyes open. Odo is being treated like some kind of prophet and you imagine this not being far removed from her mummified remains being on display in Red Square, in spite of that being the last she would want. It is also shown that Odo does not believe people will magically become good when they are removed from the profit motive, nor that the non-egalitarian impulses and language will be removed.

But the important point here is that doesn’t necessarily matter, the important part is to try.

In the introduction to this story in The Wind’s Twelve Quarters, Le Guin describes Odo as one of the Ones Who Walked Away From Omelas, Another story of hers which, I feel is, 1) the most famous and 2) the most misunderstood. Omelas is not some fantastical thought experiment, it is the globalised society we live in. And walking away does not mean becoming some rich hippy who drops acid on a hillside, it is rejecting the rules of society in which we live in order to make it better.

I myself am not an anarchist (I am even more cynical than Odo about human nature) but even with the flaws highlighted I find the joy of the imagery as it is shown is beautiful enough to drag me along, whether than be people riding through the sewers or the bank turned into a lodging house.

I could easily write a 1000-page book just about this story and novel, and all the reasons I adore them, but I will instead leave with a section from one of my favourite songs, that I was reminded of whilst reading it, The Shelter Song by Mike Hart:

As I walked round the town,

a thought came in my head,

look at the size of George’s Hall.

And those cathedrals on the hill,

they never drink their fill,

And frankly I was rather appalled.

Let’s chuck out the altar

and burn all the pews.

Put bunk-beds in the nave.

And then God may shout:

“At last they’ve seen the light!

Interpreted the message that I gave.”

Brian:

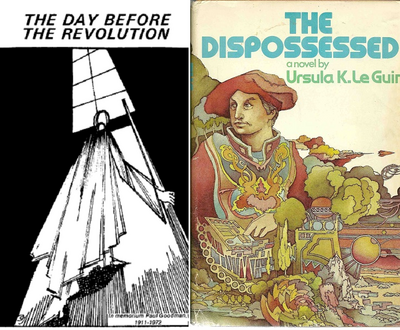

Unlike Kris, I am an anarchist, of a sort. Some kind of libertarian socialist. It really depends on the time of day. My politics are thus closer to Le Guin’s, and yet ironically as my worldview has shifted closer to hers, I’ve also become more critical of her writing. Granted, as someone who’s loved reading science fiction since they were in high school, and who gravitates towards “the classics” (which in SF is a really gelatinous and moody term), I was predisposed to get into Le Guin. I especially really enjoy her short fiction, which I do think holds up better than her novels. I still really like “The Day Before the Revolution” on a reread, but I have to admit when I read The Dispossessed years ago, I was disappointed.

Reading “The Day Before the Revolution” nowadays, it’s very hard to not see Odo as Le Guin anticipating her own ascension to a kind of secular godhood among genre readers, which in the ’70s was already taking place. She had won a Hugo and Nebula for The Left Hand of Darkness, a Hugo for The Word for World Is Forest, and was about to win another Hugo for “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” She would become one of those few universally respected writers in the field and her reputation has become so inflated that the Library of America recently put out a volume of her poetry, despite nobody really asking for such a thing. The ground she walked on became holy; it’s a bit disgusting. Similarly, Odo, who in this story is elderly and a widow, looked after by a young man she basically admits to having a sexual relationship with, seems to anticipate herself becoming a semi-mythical figure after her death, as indeed she does by the time of The Dispossessed. She resents it, yet feels powerless to stop it; and maybe so did Le Guin. But then did Odo actively play a part in her own enshrining? Did Le Guin? Should we hold her sacred-ground status in the field against her, and if so, how much? Did she know what she was doing?

I respect Le Guin. I think it’s hard not to, even if one disagrees with her politics, as indeed most readers would on some level. But what I like about Le Guin at her best is that she can put on a number of hats, sometimes within the same story. You might get Le Guin the feminist, or Le Guin the anarchist, or Le Guin the environmentalist, or Le Guin the Taoist, and so on, and they’re not mutually exclusive. “The Day Before the Revolution” is very feminist and anarchist, but it’s also bitter. Le Guin knows, and we know, that the libertarian socialist utopia, both as a narrative and as a notion of a society that could actually exist, basically died with the 19th century, with the Bolsheviks then nailing its coffin shut. Despite the bitterness, though, she at the same time tells us (by “us” I mean left-leaning people, not just anarchists, who genuinely hope for a better future) to keep the faith. So, we must, or should.

Rose:

There was a wall, conceived of as a means to explain a divide in ideology between entirely fictional people on far away worlds that felt as vibrant and real as our own terra firma. So, the book starts, continues, and ends with a very stubbornly immovable wall between visions of the future, but if Le Guin means to remind us that change is slow and often bears little fruit, she also uses her wall and her scientist and her bald headed or oddly dressed or futuristically primitive masses to remind us that change is still waiting for us to make it. I love this novel because it is really about the human desire to desire things and hope for better. There is no lollygagging, however, about the beautiful pieces of that process and very little sidestepping the bad. It feels honest and straightforward and political but not prescriptive in perhaps the way that others feel it has been. I like that it is, before all else, a story about a man and the people around him learning to view the alien as just another part of their world. The politics lean left about as much as the tower of Pisa stands upright, which is to say that I suppose it will always depend on your perspective. To me, Le Guin explores radical concepts with a hesitation that is honestly quite bold for the time of penmanship but likely only moderate among present day leftist authors. I really enjoyed the read.

One thing that both the short story and the novel do very well and which would greatly benefit the studying authors of today’s age, is the presentation of the mundane through an absurdist lense. This starts quite early on in the novel with the first conversation with the doctor. Terms like “professionally deaf” remind us vibrantly that despite the absolute alien life they lead of space travel, the human experience persists. At the same time heightened attention to actions we may consider normal reveals them to be utterly ridiculous. Like our meticulous removal of hair, especially for femmes in our society, or the disposal of products which are cheaper to replace, or the existence of diseases that could easily be cured. The short story takes similar approaches with feminist themes to help the notion of dissent be understood as odd or even alien despite our innate human understanding of that feeling.

All in, I love Le Guin. I always have, I suspect I always will. She is a master wordsmith capable of taking a large number of conflicting personalities and ideologies, shoving them into the pages of her novels, and maintaining their characters as vibrant, absurd, and very very real.