Brian:

Truth be told I was a little worried we would not cover Sterling in the ’80s, because in my mind’s eye he’s a quintessential ’80s SF author even though he would do some major work later and even win a couple Hugos. But for the whole of the ’80s he got the always-the-bridesmaid-never-the-bride treatment. He got at least one Hugo nomination almost every year from 1983 to 1990 and he lost every time. I would’ve picked “Dori Bangs” over what won that year, but that partly has to do with my intense dislike for the Charnas. “Our Neural Chernobyl” lost to Mike Resnick’s “Kirinyaga,” which does not speak well of readers’ tastes in the late ’80s. But did it deserve to win? Not exactly. It’s a fun little pseudo-book review that isn’t cyberpunk (like a lot of Sterling’s fiction actually), but it does have a couple hallmarks like designer drugs and messing with human (and animal) intelligence.

Unlike “Kirinyaga,” which is like a time capsule but in an uncomfortable way, “Our Neural Chernobyl” is veeeeeery latter half of the ’80s but still entertaining. It does not take itself that seriously, despite the implicit foreboding tone of the title. It’s almost admirable how in ten pages Sterling manages to cram in some real ’80s-isms like illicit drug use, AIDS, and of course the Chernobyl disaster which would’ve been very recent history. Specifically Sterling uses the Chernobyl disaster as an example of when human ego and lack of concern for safety result in a negative turning point in human history. The difference is that while some things got irreversibly borked, there are a couple positives to come out of it. It’s not a hopeless situation. Sterling sometimes tries to be a hehe haha funny man, with mixed results, but I would say this sort-of comedy works.

Not much else to note. It’s enjoyable, but it’s also a story that doesn’t really have a plot, nor does it have characters in the conventional sense. All the better that it does not overstay its welcome.

Kris:

There was clearly something in the air at this time as Eileen Gunn’s Stable Strategies for Middle Management is also a darkly humorous biohacking story. Apparently the term was first recorded around this time in print in Michael Schrage’s Washington Post piece Playing God in your Basement, which means he was probably familiar with the concepts but also may be why he uses “Gene-Hacking” instead, to match with the term “Gene-Jocks”, Michael Schrage uses (also a wonderfully cyberpunk term).

As to the story it might well have got my vote, as I am a big fan of stories that make a consideration of the mode of storytelling to build the world. Here he uses a non-fiction book review, the kind you might see in the back pages of late 60s New Worlds or 80s Interzone (both of which magazines Sterling praised). These kind of stories I feel have the advantage over the usual first person or third-person omniscient. If done well they allow us in a few pages to get a glimpse of the world not just from what is told but how it is told.

Here we get the explanation of what happened in “Age of the Normal Accident”, where “Chernobyls” become the standard term whenever a criminally negligent technological disaster occurs, much as “-gate” is regularly applied to political disaster. The contents of this story could easily seem like an updated version of Poul Anderson’s Brain Wave in a normal telling. What he does do, though, is cleverly map out the world through the telling.

One example, we see that in the 1990s these kind of disasters are common but appear to primarily affect poorer countries (Indonesia, Pakistan, Kenya are mentioned), however, the titular event affected the United States. It is noted that shortly afterwards we had the “New Luddism” movement, which it is clear the reviewer disdains and dismissed in favour of the “Open-Tower Science” of Dr. Hotton. Even though it is not clear what they refer to exactly, it is reasonably easy to work out from names and clues. Luddism is the philosophy against machines replacing skilled labour in the early 19th century, so New Luddism would likely be a reaction against these Chernobyls hitting the US and be against the kind of technological progress coming at the expense of people. With Open-Tower Science being a response, this seems to be an antonym of Ivory Tower, so a way of doing science that is not isolated from people. However, how dismissive of Luddism the writer is and how he even tries to see positives in the Neural Chernobyl, we have to question how positive the results really are and if the beliefs that biohackers are still operating in secret are actually true.

Another is the casualness of his description of Bugs being not that different from others in the North Carolina research triangle:

“His father was a semi-successful free-lance programmer, his mother a heavy marijunana user whose life centred around her role as “Lady Anne of Greengables” in Raleigh’s Society for Creative Anachronism.

Both parents maintained the flimsy pretense of intellectual superiority, impressing upon Andrew the belief that the family’s suffering derived from the general stupidity and limited imagination of the average citizen”.

Now, firstly this kind of armchair psychologising is very common in these books and adds to the sense of verisimilitude. Secondly, it creates a sense of the kind of community this is, where free-lancing and drug use are common place but also there is a sense of discontent at this state of affairs. That they probably would prefer to have more stable livelihoods. Thirdly it shows us the author looks down on these kind of people, that even within the Open-Tower science movement, there is still plenty of snobbery and elitism.

I could go through this throughout the vignette but it is all to say there are layers to the tale, where we are detached from actual events by four layers:

Our lack of context reading

|

V

The review

|

V

The book

|

V

The actual events

Each of which is provided through its own lens and prejudices that compound the complexity and make more mysterious what actually happened. As I said before it would be easy to do a Brain Wave style tale with this. You could even make it cyberpunky by have it written by Bugs, who seems like the standard kind of narrator for these tales. But that would also not be as interesting as what we get here.

In terms of if this is Cyberpunk or not, I am not sure that I have seen anything written in the Blade Runner\Neuromancer\Terminator style that would become the core idea of what the genre was. His novels explore diverse ideas like Climate Catastrophe, Politics, Steampunk etc., whilst even his most commonly cited stories cited as Cyberpunk are not in the usual focuses. Mozart in Mirrorshades is alternative history, Red Star Winter Orbit is about the end of the space race, Green Days in Brunei would probably be called Solarpunk today.

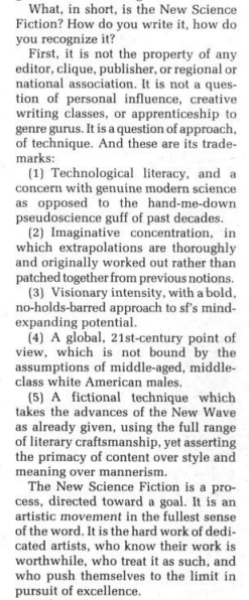

But then he seemed to consider a much broader idea for Cyberpunk. In his Essential Cyberpunk library he lists the very New-Wavey Deserted Cities of the Heart, and his own far-future Space Opera, Schismatrix. Whilst his manifesto on the “New Science Fiction” has a very broad remit:

My point being we may not consider it to be Cyberpunk but Sterling may well have done. Throughout the 80s in particular the true meaning of the term was debated. In fact some during that time argued that Neuromancer and Blade Runner were not true cyberpunk as they called back to the 20s and 30s aesthetic rather than the punk aesthetic you got in others like Shirley and Bethke.

Brian:

I do think Sterling was a more versatile writer than Gibson, at least at this early point, so naturally Sterling’s definition of cyberpunk would be broader. It shows his range that he wrote the Shaper/Mechanist stories and also “Dinner in Audoghast” and “The Little Magic Shop” around the same time.

Not to mention “Dori Bangs,” which is a supernatural alternate history (or historical fantasy, whatever) despite Dozois trying to convince me it’s SF.