Roger Zelazny won sixteen awards over the course of his career: six Hugo Awards ‚three Nebula Awards, two Locus Awards, one Prix Tour-Apollo Award ‚two Seiun Awards, and two Balrog Awards. Since his death, his fame has dwindled1but in his day he was popular with readers and respected by authors andcritics. He seemed like a reasonable bet for someone whose appealmight have stood the test of time.

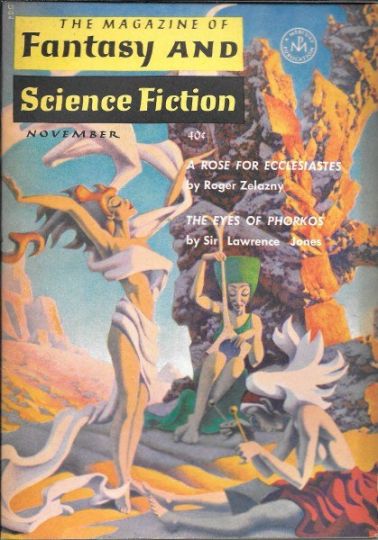

I selected 1963’s A Rose for Ecclesiastes for a few reasons. The least important is because I only recently read it myself (the story kept coming up in the context of a grand review project of mine and I got tired of admitting over and over again that I had not read it.). Another is its historical significance: this is one of the last SF stories written before space probes showed us what Mars was really like. The final reason is this story was nominated for a Hugo and I am hopeful that the virtues the readers saw a half century ago are still there.

Let’s find out!

A Rose for Ecclesiastes can be found in his collection TheDoors Of His Face, The Lamps Of His Mouth, available here.

EscapePod’s audio adaptation can be found here.

1: I was astounded to discover his Doorways in the Sand, nominated for Hugo and Nebula, has been out of print since 1991. 1991!

This story was quite ‘meh’ for me. Having studied English literature, this seems similar to many other stories written by modernist poets/authors angsting about the late 19th/early 20th century. Like the poets the narrator mentions, Zelazny seems to be going for a blend of ‘perfecting a classic’ (in this case, the meta short story) and ‘the modern future that is here will be nothing like bygone days’.

But anyway, enough of sounding like a student’s literature essay. What I mean to say is, this story feels old. As if it was written much earlier than when it was. I don’t know if that’s worse, but it’s definitely more…pretentious.

Reading this story, I get the same feeling as reading a book series – this story is like your least favourite book in the series. It’s like the one you’d want to skip over if you’re re-reading the series for fun (like not reading the 6th or 7th in the Chronicles of Narnia series — yes, I like those ones much less than The Horse and His Boy).

The whole story reminds me of the Stargate movie, told form the perspective of the linguist character Daniel Jackson. The other characters look down on Jackson a little as a nerdy character. Same for Gallinger. Jackson is the one who learns to speak with the people from this other world. Same for Gallinger. Jackson is ‘gifted’ a girlish woman. Same for Gallinger. Probably the same prevalent male fantasy.

To be fair, Gallinger is left out of the matriarchal alien society once he fulfills his role in the prophecy by impregnating the girlish dancer character.

Another weird thing very specific to around the 1950s: Gallinger uses champagne and Benzedrine. This was such an oddly specific combination I had to look it up. So first I learned that Benzedrine was a popular, commonly available and quite strong amphetamine. Then I learned that champagne and Benzedrine was specifically popularized by early James Bond. You know, in the days when baccarat was a popular way to gamble.

As for the story’s title, it’s a trade between races. Gallinger gives them a rose, literally as well as figuratively. He gives them a rare thing they cannot make themselves (a baby). In exchange, he gets Ecclesiastes (their ancient texts). It’s all a beautiful poetic sentiment. But my question is, how does one baby save the alien race? Do their genetics work differently? Isn’t the Martian/Earthling hybrid going to have a shorter life span than the Martians who can live for hundreds of years?

What I’m saying is: this whole story is a beautiful poetic sentiment. It’s a Modernist poet’s feverish daydream of alien abduction. Prod it, and it falls apart.

—Mel

I guess the best thing about this story is that it is immediately made very clear that I shouldn’t hold out any hope of either it or its protagonist having any redeeming value.

I have no interest in reading about an entitled guy who’s been allowed to get away with being rude to everyone because he’s smart. I have no interest in dealing with men like that in real life, and I certainly don’t need to read about them in my fiction. And even if the protagonist’s smugness didn’t put me off, the casual sexism and racism throughout the story would have.

I was interested when it was explained that the Martian society was matriarchal, although not overly optimistic considering the way Betty is portrayed and the language used to describe her. It turned out that my cynicism was completely deserved, since the only point of the matriarchal culture seemed to be that they seduced him with dancing so that he would father a baby. *eyeroll*

I was frustrated by the idea that Gallinger became more civil when he was involved in a romantic relationship. As someone who is aromantic and tired of romance being used to fix people, that trope can go die in a fire.

I’m also uncomfortable with the use of a Christian missionary, and trying to convert the native from their apparently misguided religion using Bible readings.

This story was annoying, sexist, racist, has ace and arophobic microaggressions, and failed to do anything interesting with the plot elements it introduced. I wouldn’t have finished it if I wasn’t reading it to review.

—Mikayla

I liked this one. It just needs a modern editor to say “no, you can’t call it ‘the Orient’ ” and maybe catch a few other questionable phrases. This story spends so little time on showcasing questionable science that I was able to overlook it. However, the more I think on it an empty, mostly vacuum desert (that wasn’t always that way) would only add to the tragedy of the Martian people. A dying civilization locked in a pressurized city beneath the surface would fit right in. As it is, they might as well be on some unexplored continent of Earth.

The Martians looking like humans was unexpected. Until Gallinger mentioned that they looked exactly like humans that is not how I imagined them at all. For some reason I was picturing rust-red skin and long thin arms. Something about the initial description of M’Cwyie’s dress. I guess panspermia is the correct theory in this universe. And recently, to spread humans to both Earth and Mars.

The thought of an entire religion based solely on writings similar to Ecclesiastes is pretty dour. No wonder the Martians were prepared to just die out.

I liked how in the end Gallinger wasn’t some grand hero who stayed to repopulate the Martian race. I’ve read stories with that kind of ending, kind of wish-fulfillment fantasy. Everyone is more reasonable in this one. The Martians decided to live, so they’ll ask for some human medical expertise and maybe put in some orders to a sperm bank. This wasn’t a tale of how amazing humans are, saving the poor Martians. After their prophecy was fulfilled, the Martians decided to save themselves.

I kind of feel bad for the future of the Martian race though, based on humanity’s track record of contact with lower-technology cultures.

—Jamie

I really hated this story… at times. At other times, it confused, amused, and frustrated me. Maybe it was just the mood I was in last night as I read, but the story definitely took me on a ride, which I could appreciate.

The story had some of the elements of science fiction I find annoying, like having weird technology not fully explained that I don’t really understand. But I guess science fiction minus otherworldly/futuristic stuff is kind of just fiction, so this time I was willing to let that slide, suspend my disbelief, and keep reading.

The characters (well, the main character) was great. I loved seeing Mars and martian culture through his biased, flawed, and arrogant eyes. All the other characters seemed fine, although you never really get to know them, since the narrator is just so self-centered.

I really appreciated the way the narrator engaged with the martians. He studied them without ever talking to them. He assumed knowledge of them without ever asking them about their past experiences. He saved them from something he knew nothing about, since he was a white guy from Earth, and they were a female-run colony with philosophical beliefs that differed from his own. He sort of put his arrogance aside because he fell in love with one of them… but still tried to impose his beliefs on the entire society anyway.

As the story went on, my annoyance with the author and the story increased. I knew exactly what kind of story it was going to turn into – White Guy Saves Women Who Don’t Know Better From Themselves. I hate-read the last few paragraphs of the story. And then, at the end, I was surprised. I am actually even considering re-reading this story to see if I missed any clues alluding to the ending because I was so sure I knew better than the author, that I was positive I knew how things were going to end. If that was Zelazny’s end goal, it was well played. If he never intended to blind his readers with fury, and just wanted to make a point, well that’s pretty cool too.

—Lisa