Kris:

I cannot find my physical copy of best fantasy of the year I was originally looking for but I have it also in my copy of Modern Fantasy by Women.

A very useful volume this. Was a good investment.

One point to start this on. I hadn’t recalled how much Christianity plays a role in it. The ending reminded me of the original HCA version of The Little Mermaid, but even more so. I mean how many fantasy stories end with someone literally having their soul saved by Jesus (that aren’t by CS Lewis)?

This seems to have been a time where Fairy Tale retellings were coming back in to vogue, it being the same year as Angela Carter’s Bloody Chamber and the year after Robin McKinley’s Beauty.

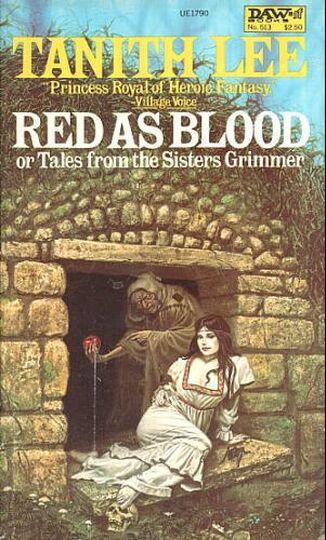

The thing that makes this stick out most for me though, is just how beautifully it is written. Tanith Lee often seems to be overlooked among the 70s wave of women writing SFF (I wonder if partially that, like most British writers of the time, she was largely published in paperback anthologies and from the paperback-first DAW books). But that is a real shame as I just love sinking into the language.

There also just something charming about the way it effortlessly weaves vampiric and fairy tale lore together.

Brian:

Ironically having read this story before and even reviewed it not too long ago made it hard for me to sit down and gather my thoughts a second time. Of the Lee stories I’ve read this one is probably my favorite, and it’s also one of the first “fairy tale retold” stories I’d recommend to someone who is (understandably) unsure about the form’s appeal. Despite involving a vampire this is not a horror story, but dark fantasy that takes on an increasingly allegorical flavor as it reaches the end.

In a way I don’t have much to say about it that I didn’t already say elsewhere, for one because of its length (it’s not even ten pages), but it’s also the kind of story that speaks for itself. “Red as Blood” was, as Kris mentioned, an early example of modern authors putting a dark twist on classic fairy tales, which is funny to consider given that many of these classic fairy tales were already quite dark and morbid. This is not so much the case with “Snow White,” which could do with a spooky twist. Here the twist is that Bianca (Snow White) is a vampire, having apparently inherited the gift from her biological mother, although her stepmother, the Witch Queen, will have none of it. The Witch Queen is a curious figure since she is somehow both a witch and a devout Christian, who takes big issue with Bianca’s aversion to churchgoing and Christian iconography. The Witch Queen also makes a deal with Lucifer at one point, so she can’t be that big of a Christian.

I had forgotten that Bianca, who in this story is barely a teenager, seduces the much-older huntsman and lures him to his doom. I’m not sure if Lee’s trying to say anything here or if this is just a byproduct of how in ’70s SFF there was a strange tendency for authors to write adults as having sexual relationships with people who are not even old enough get a driving permit. At least with “Red as Blood” nothing explicit happens. Otherwise, this is a pretty timeless version of the story that would probably (hopefully) still get printed if it were submitted as a new story today. Lee really goes out of her way to capture a certain poetic prose that both was and is kind of a rarity in fantasy writing.

I still have not really made sense of the ending, in that I’m not totally sure what Lee is going for, or if her use of Christian symbolism is meant to be taken as sincere. You can’t always tell with these things. I have no clue if Lee was religious or not, and it’s totally possible (indeed it has happened before, see Shakespeare, also Mamoru Oshii and Hideaki Anno) for someone who is irreligious to use religious symbolism as a kind of storytelling flex. There are good and bad ways of doing such a thing, but I think Lee pulls it off in pretty good taste here.

Rose:

A strikingly feminist revision of the Snow White fairytale, Red as Blood is as unsettling as it is profound. Written in 1983, it stands as a gothic allegory for the dangers of idealized femininity in its era, while remaining relevant to the present day. Atmosphere and religious overtones set the scene for a tale centring on the horror of beauty as a devouring force. Lee uses vampirism to cleverly discuss the psychological and physical costs of being a woman under a patriarchal system that values women for their beauty above all else. At the same time, Lee intentionally overrides and reimagines previously two-dimensional characters to recenter women in their own story and return agency and nuance to both Bianca and the Witch Queen.

Lee begins her story during Bianca’s gestation, when her mother gives everything to ensure her daughter will be beautiful: lips as red as blood, hair as black as ebony, and skin as white as snow are all traits of beauty. Her mother is also subject to the vampirism disease, which has turned her cold and manipulative. This is a generational illness passed from one beauty-obsessive mother to her child. At the same time, this illness grants both mother and daughter agency and power, turning them from prey animals into predators who grasp agency with both hands and use it to manipulate their world.

The wasting disease that follows in their wake should, in my opinion, be read as an allegory for eating disorders, which were approaching crisis levels in the 80s when this was written. Similar to modern celebrities in our modern age, royalty set trends when they were in power. Bianca and her mother, both being so openly vampiric, lead to a wasting disease in their nation that I believe can be attributed to the beauty standard they set and the cost of their illness. This theme is further supported by references to Bianca being hollow and follows well from her inability to see herself or allow others to see her in a mirror (a common symptom of disordered eating is body dysmorphia). In my opinion, it is no accident that Bianca is associated with both eternal youth and deadly decline: she is the impossible ideal that simultaneously draws admiration and causes destruction.

The stepmother (long vilified in traditional versions of the tale) becomes, in Lee’s hands, a nuanced leader who seeks peace and safety for Bianca and her people. Though she is described as beautiful, she is not defined by her physical characteristics. The stepmother in this tale is known for her capabilities as a witch and lauded as a good queen who does what is best for the people and for Bianca. In a culture which predominantly values women for being young, thin, subservient, and conventionally attractive, the stepmother choosing to ask for help to be transformed into an old balding woman of little beauty and then not immediately reaching for the potions which could reverse that physicality is significant. The Witch Queen is an embodiment of what we may now recognize as the body-neutrality movement. The story, in essence, tells women to forgive themselves, find peace with aging, and value themselves less for the strict disciplines required of disordered eating, to focus instead on their skills and abilities.

Red as Blood endures because it tells a truth that still resonates. In today’s world of social media filters, wellness fads, and endless scrutiny over female bodies, Lee’s story feels less like a period piece and more like prophecy. With timeless prose, strong imagery, and active characters, Lee has spun a tale of innocence and beauty into a razor-edged critique of the violence those ideals can inflict. Lee is, in effect, asking: What are we willing to sacrifice to be beautiful?