Rose:

From his insistence on writing stories about naked children and depicting women as rare character types, to his continued exploration of the gift/curse complexity of genius types, Mikal’s Songbird is an excellent example of exactly what I have come to expect from Scott Card. This being the precursor to Scott Card’s novel, Songmaster — which I have read and enjoyed for what it is — I think it is not very possible to separate my critique of the short story from my critique of the novel. As such, please bear with me through my (as always) feminist critique of the works more collectively.

Mikal’s Songbird offers a haunting meditation on beauty, emotional power, and exploitation through the lens of a gifted child singer. While the narrative is steeped in music and subtle tragedy, and the prose is poignant and believably stunted by the realities of having a child narrator, the interesting part of the story (to me) is how it discusses and portrays power and its consequences. Scott Card makes very clear from the beginning that this is a Power Over universe as opposed to a Power With, Power Through, or Power Of universe. What do I mean by that? Well, I don’t have the time to write a dissertation here, but I’ll drop a table below so you know what I am talking about. Please note that these are not necessarily the only types of power, but these are the ones you should know to understand my critique.

Ok, so let’s talk about it. This story makes core assumptions about what is required for stability and, in doing so, perpetuates the ideas and systems that continue to consume the vulnerable (i.e. patriarchal systems) are essential and for the greater good while still trying to condemn their consumption of the vulnerable. Sure, on the surface it’s about the terrible gift of genius, but in reality, it hinges on this political dissonance.

Ansset is fundamentally vulnerable and holds very little power himself. He does not have power over anyone; holds minimal power through his connection to Mikal; is disconnected from opportunities to hold power with others; and has lost the power of his gift due to his own marginalization by those who hold power over him and wield power through the use of him.

The only group that appears to hold Power With others is the resistance, who are painted as villains for threatening the stability of the empire and creating dangerous unrest. Meanwhile, the government that does exist hinges on the power one man holds over the rest of the population by exerting power through systems like the military and the palace guard, and handles opposition from power with groups by wielding the power of culture, stories, narratives, and (critically) of Ansset. However, though this regime is subtly criticized for its cold and harsh ruling, it is also portrayed as essential and, more or less, for the greater good. This can be seen in the sacrifices Mikal makes to keep the empire going after he is gone being treated as heroic and noble as well as the general discussions about the resistance, the role of violence as an effective and necessary tool, and the importance placed on maintaining the systems that support this Power Over approach. This portrayal undercuts Scott Card’s conflicting critique of how the vulnerable are taken advantage of.

We are supposed to feel badly for Ansset and covet his freedom and safety throughout the story. We are supposed to gasp in horror at how an innocent little boy could be so unjustly co-opted and used to his own detriment by the people in power. We are supposed to agree that he deserves better, but not agree so much that we understand and sympathize with the resistance. The problem of Ansset is portrayed not as a systemic issue or a feature of the power structures in place within the world, but as a personal moral problem. Ansset is, of course, not the amoral one in the story, but the story implies and even outright discusses how the problem is that people want to use him and if they could just personally have more empathy then things would be better. For example, we are shown that Ansset is treated better by Mikal on return to the palace than by the palace guards because Mikal loves Ansset instead of seeing him as a potential weapon. Even after Ansset is discovered to have been specially trained to commit atrocious acts of violence, he is forgiven and loved which allows him to be shown love and care. This is a personal connection from Mikal that is the saviour, not a system built with forgiveness in mind. The story, from my perspective, seems to say people should be nice to each other, without asking, Why aren’t they?

While Mikal is empathetic and shows love — the thing Scott Card seems to emphasize so much as the personal change that can save the vulnerable — he is also the biggest supporter of the system which creates vulnerable people. By supporting the empire, Mikal is actually showing how personal kindness is not the same as saving the vulnerable nor is it adequate to make meaningful changes in the quality of life his citizens experience daily.

Now, there are two ways to interpret this: the easy way, and the nuanced way.

The Easy Way

The existence of these two opposing views in Scott Card’s work stems from his beliefs about power conflicting with his desire to send out a message about helping the vulnerable and recognizing their struggle. Specifically, his belief that power over (with help from some coerced forms of power through and power of) is essential to creating and maintaining peace conflicts with his belief that vulnerable people can be saved through kindness and empathy. The conflict exists primarily in Scott Card’s inability to recognize the conflict in his belief systems or messaging. This means the conflict is unintentional and creates a story with disconnected morals and beliefs that will never be harmonious and which will perpetuate continuing the systems that cause harm while taking a moral high ground about helping the vulnerable that might help himself and readers to feel better about themselves, but which doesn’t actually do vulnerable people any good.

The Nuanced Way

This story is a critique of the “Easy Way” narrative I outlined above. Scott Card is not actually making the argument above, but asking his audience to see and critique the above narrative.

Why it doesn’t matter which way you interpret it.

At the end of the day either the “Easy Way” narrative is what Scott Card was intending to communicate to his audience, or he did a very bad job of providing the tools his audience needed to recognize that he was critiquing the “Easy Way” narrative and stimulating genuine dialogue about why the “Easy Way” is a flawed world view. Mikal is undeniably “the good guy” and while the other puppets of the empire are portrayed as flawed and possibly untrustworthy, they too are “the good guys” of this story by virtue of their work being important to the maintenance of the empire. The footing to critique the “Easy Way” narrative is not provided by Scott Card.

Do not mistake this as being my way of saying that I want him to spoon-feed his audience the answers. Scott Card has tried that approach in the past with far more harmful ideologies and narratives (see Petra in the Shadow of the Giant and subsequent Shadow series books for a great lesson on how not to treat female characters in your work and how to badly spoon-feed breeder-based, misogynistic, and superior race ideology to people under the guise of sci-fi), I could not call his spoon-feeding attempts good or effective. However, footings must be provided to help guide the readers to the questions your work is trying to ask and help them to analyze and understand the perspectives you are putting forward. (For an excellent example of how to do this, I recommend reading any Ursula K. Le Guin work.) As a result, whether it was intentional that he should portray the root cause of vulnerable people as being essential while portraying vulnerable people as needing saving or whether he was trying to do it to show why those ideologies are in conflict, the end result was the same: Orson Scott Card wrote a short story (and subsequent novel) which failed to find a cohesive moral, stumbled through its own themes and arguments, and presented a flawed and underdeveloped narrative.

Did I like the prose? Yes, about as much as I ever have; which is to say middlingly. Did I find Ansset to be a compelling character? More so in Songmaster than in Mikal’s Songbird, but overall… yeah. Did I think the politics were compelling and the tactics fun to read about? Kind of. Did I find the story to be particularly good? No, not really, and I can’t say I have ever felt that its successor, Songmaster, was worth revisiting after my first read either.

Altogether, the story is entertaining; it is a good way to spend a short amount of time lost in another world. However, it seems to have lost its way starting sometime just after conception. I find myself at a loss for more in-depth world building, and when I received that world building in Songmaster, I found myself at a loss for how anyone could think that this world made sense. Should you read it? Maybe, but only if you promise not to internalize ill thought-out attempts at discussing power and its consequences.

Kris:

There are elements of this that feel in my wheelhouse (or songhouse), the political intrigue, the Manchurian candidate style antics, the mix of different period references but it never came together for me. Part of it I feel is Card’s style. I do not find it easy to get along with and found myself rereading passages to ensure I understood them correctly. There is also the related issue that Card has a specific small set of tools I have seen him use multiple times before. If you are a fan, you will probably enjoy yet another of his tales in this style. As I only kind of liked Ender’s Game I found this tedious (in interview he said he specifically wrote this in imitation of Ender’s Game to try to duplicate his former success).

But then there is also the fact that I don’t think is particularly well constructed. Among other issues, situations jump about too much. I didn’t get a full understanding of the characters and I am not sure I understand the purpose of the frame.

I think this is one that Card’s fans will enjoy but it is not particularly rewarding reading for others.

As a side point, do we think we are meant to think there is a sexual relationship between Mikal and Ansset? I feel it is hinted at, but if it is stated outright, I missed it. On the one hand, it’s a 12-year-old boy and an old man, so ewww. On the other I see a lot of parallels with the Roman Empire here where it wouldn’t have been considered as strange.

Rose:

I did not pick up on a relationship of sexual nature between Mikal and Ansset but I did pick up on (and absolutely found textual evidence of) an abusive father-son type of relationship between them. The power imbalance and requirement of Mikal’s position to maintain power over Ansset as well as weild the power of Ansset’s gift to maintain his position as a supreme being makes the relationship genuinely unstable. Their relationship can easily be categorized as abusive regardless of the actual love or lack there of that Mikal has for Ansset and vice versa. I 100% agree with you that the relationship is Not Good, but I did not pick up sexual undertones, although it’s hard to tell all the time with Card as he does love to have children’s naked bodies centralized in the story.

Kris:

Yeah I think abusive either way is probably the best way to see it. I definitely think whether it is sexual in nature Mikal does not truly love Ansset, but would be using him.

Riktors does ask if Mikal slept with him which Ansset denies, but we also know Ansset is very niave and doesn’t know what people mean they refer to him as a catamite, so it could still have happened.

But, anyway, I don’t want to go too deep into this line of thinking and just say, whatever is happening between them is definitely not okay.

Rose:

Agreed, happy to hear I’m not the only one who sat back and went, wtf?

James:

FWIW, when I read the fix-up novel way back when, I assumed it was a tragic gay story, of the God will smite you if you act on the urges God gave you variety. Thinking too hard about those urges may count as acting.

Rose:

It’s hard to say from a moral standing if thinking bad thoughts is the same as doing, especially if the act of thinking the thoughts results in an abusive relationship anyways. Personally, no matter how you hash it, this story is messed up. It’s depressingly sad and yet not for the reasons Card seems to think which actually just heightens the sadness of the story. I didn’t really like it and have mostly stopped reading Card’s works since recognizing these constant moral and value flaws that are so prevalent in his work.

Much rather read Weir who also tells stories about smart people (arguably not genius types but close) in crazy circumstances. At least his characters aren’t naked children and he treats women and girls in his stories with respect and dignity (especially in Project Hail Mary, but also more generally).

Brian:

First thing I should say is that we really ought to go back over what we said and make sure we spelled Mikal’s name correctly, Because it’s Mikal and not Mikhail. So it’s “Mikal’s Songbird.” I’m pretty sure I also made this mistake, and I don’t know why we all insisted on misspelling his name.

James:

15 instances of Mikhail for Mikal fixed, along with (once Brian pointed it out) 22 instances of Ansett for Ansset. I get why the first, but not the second.

Brian:

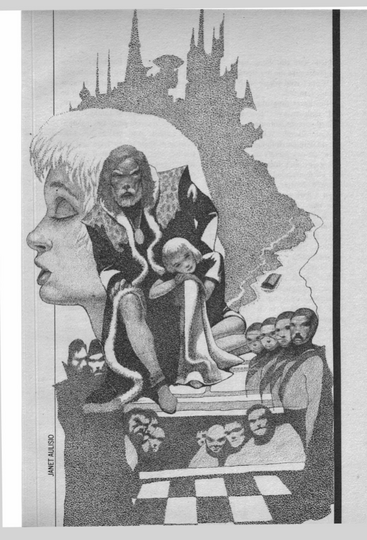

Anyway, very funny that we’re having this posted early in Pride Month, because of Card’s raging homophobia but doubly because “Mikal’s Songbird” is, for all intents and purposes, a queer narrative. It was written by a homophobe who may or may not be a deeply closeted gay man (I would not put forth outright that Card is a deeply closeted gay man, but if I was to say such a thing, there’s plenty of circumstantial evidence…), but that doesn’t make it any less queer. It is, textually, about a boy who is subjected to sexual abuse by older man, and who has a surrogate father-son relationship with a much older man who may or may not harbor romantic (if not sexual) feelings for him. In the Ender series there’s child abuse, and arguably a subtext of pedophilia, but in “Mikal’s Songbird” the pedophilic aspect is not only text but part of the plot. The fact that there are no women to speak of, so that Ansset’s world is full of men who have power over him, only reinforces the problematic gayness.

When I started reading this story I have to admit I was confused as to what was happening. My major issue with this story is that Card spends very little time establishing what kind of future world this is, or even if we’re on Earth or some other planet. As said before it’s basically like the Roman Empire but in space, which is to say it’s like the dying galactic empire in the Foundation series. There’s a curious mix of ancient attire and ritual alongside some futuristic tech, but Card doesn’t really go beyond that. Maybe it’s not necessary. Once we’re settled into the central conflict, that Ansset is Mikal’s prized Songbird (a kind of bard in training) and has been recently rescued after having gone missing for five months, a period Ansset has no recollection of, the stage is set. The twists, except for maybe the one involving the new Captain of the Guard, are obvious, but what had my attention was what was not so obvious. There’s a power struggle between Mikal, the Chamberlain, and the Captain (both the old and the new one), all with different intentions for Ansset. It’s political intrigue, sure, but it’s also a compelling (for me) moral play about trying to make the best of a bad situation, or about trying to find moral refuge in a space that is ontologically immoral. (edited)

My second biggest issue, although it’s more of a quibble, is that Card’s style can get rather precious, granted that this is not an issue unique to “Mikal’s Songbird.” One of Card’s worst habits (aside from a didacticism that got worse as he got older) is a tendency towards going overboard with the sentimentality. There’s something kind of twee about Ansset’s innocence and his relationship with Mikal, who himself is not what you’d call a good person, almost by his own admission. Mikal tells Ansset at one point that he’s done horrible things and will do more horrible things in the future, by virtue of being emperor. A more left-leaning writer, or rather someone more concerned with systems than individuals, would’ve interrogated Mikal’s moral greyness more, but Card is mostly concerned with individual actors and their own person demons. We’re basically told that Mikal is an alright guy, even though he has blood on his hands, because at least he’s not a pedophile; or if he is he at least never acts on his urges (that we know of, anyway). Of course, because Card is a dumbass he also thinks homosexuality and pedophilia are on the same moral playing field, which is to say he sees both as an affront to a God who probably does not exist.

I liked “Mikal’s Songbird” the most out of us, which is unfortunate because I was hoping to dislike Card’s writing even remotely as much as I dislike him as a person. But every time I return to Card’s pre-1990 work I’m drawn back in again. I think, while the seeds of what he would later become are already there, Card in the late ’70s through the ’80s had a certain magnetism. Even if you don’t think this story was worth getting high spots on the Hugo and Nebula ballots, plus the Locus poll that year, you have to admit it’s compulsively readable; despite being a solid novelette it went by quickly for me. Also, while it has problematic elements, it’s somehow no less problematic than a lot of SF being written at the time, including stuff by actually queer writers.