Rose:

OK, thoughts:

The story is compelling and I like the descriptors used. They make me feel out of place and clunky which helps me connect to our narrator and main character. The story itself feels like if kitchen sink realism were explored by someone who has never seen a kitchen sink which is a really interesting way to construct a story. I come to literature from the rich world of French poetry, which my grandmother read to me most nights as a child. The French poet in me leans into the way that the prose others the reader. Word choices, intentional sentence splices, and confusing verbiage leads me to feeling disconnected from the world and its inhabitants. We get very few full descriptions of people, places, events, etc… most of the world building happens in the minuscule. For example, describing Juao’s horned toes, and the colours of his smile, but otherwise telling us only that he does not look his age. It leaves me with the impression that there is a normalcy here which I could not understand. I like also the fascination with the bête that the author encourages. Each character and location is some grisly thing made monster or to be made monster. The godchildren are mostly discussed as characters made to be future aquatic beasts of medical science, future combatants against the unknown forces the amphimen are deployed to tend. Similarly, Ariel is noted for being beautiful but the traits that we are told about are mostly foreign and could just as easily describe some dangerous siren creature in a Lovecraft novel. I think the plot explores the bête and its relation to human emotion which I respect. What I think the story fails to encompass is the relation to characters. I want to care more about the people who populate a story, but I want that to a much larger extent when I am reading a story whose plot is somewhat insignificant. Due to the kitchen sink realism and snapshot of a life approach the plot is more of a backdrop to a character study and concept exploration. Unfortunately, while the concept exploration was well done, I do not feel I could study any of the characters in this story with great depth. The piece is devoid of a connection to the feelings, thoughts, and even situations of the characters. I do not feel grief for Ariel who has lost her intended. I do not feel dread from Juao when his children leave for amphimen training. I feel some frustration from our narrator at the effects of his injuries, but have no connection to his inner world and so do not feel the tension or the exclusion or the adaptation struggles of his life. All in I feel the piece is strongest in its prose and its exploration of the human beast. I enjoy its commitment to othering the reader from ever truly understanding or being a part of the world it is set into. I think it is enticing in its first few paragraphs in an exciting way. I also feel it fails to be a piece I will read or think about again beyond the scope of this project because it prioritized otherness over developing audience connections to the plot or the characters. Overall that choice made it less effective as a character study and obscured its meditations on conceptions of loss, grief, immensity of obstacles, community, and change. As such I would say this is not a particularly enthralling piece of SciFi for my tastebuds though I do think the writing style is distinctive.

Brian:

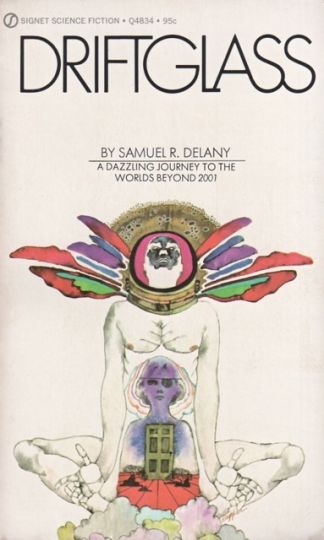

It’s about 8 in the morning here, or as the Brits would understand it, just past noon. Thinking about Delany, who by the time this post goes up will have turned 82. I was thinking about John Clute’s introduction for the Tor Essentials edition of Michael Swanwick’s masterpiece, Stations of the Tide. Swanwick’s novel is very Delany-esque, in its mythical implications, its freewheeling sexuality, and its attempt at putting us current-day landlubbers in a setting so far-future that we would scarcely recognize our own descendants. Incidentally both Stations of the Tide and “Driftglass” allude rather strongly to Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Caliban is half man, half beast, being the son of a sea witch and seemingly without a human father. He is not entirely comfortable with the sea, nor with the island he’s forced to share with Prospero and Miranda; he is amphibious. Cal(iban) likewise is one of the “amphimen,” biologically experimented on so as to have gills that let him stay underwater for long periods. Like Caliban he’s also disfigured, although Delany is a lot more explicit as to how (maybe too much, but put a pin in that). (edited)

This is my third or fourth time reading “Driftglass,” and somehow in my memory I always think of it taking place on a different planet, which speaks to the sheer otherness of Delany’s future America. As is typical of his early work he hits us with a shotgun blast of little ideas that individually don’t add up to much, but which form a whole greater than the sum of their contributions. My favorite little bit, which does not further the plot at all (admittedly the plot is loosey-goosey), is the store products that talk to the would-be consumer. It conveys an alienation that appears in other ways, such as the generation gap between Cal and his godchildren, and indeed Cal and the younger Tork (the able-bodied amphiman who reminds Cal of how he was before “the accident”). I think the story’s coldness is intentional, although I think Delany balanced this with actual human drama better in “The Star Pit,” which he wrote around the same time. I do have a couple gripes. I think too much is made of Cal’s disability and that his angst being overtly tied to said disability is not one of Delany’s better character-writing moments. I also think Ariel is not totally convincing, which is a problem early Delany had with writing female characters; if they’re not perspective characters like Rydra Wong in Babel-17 then they come off as strangely empty and aloof. Had Delany leaned more into the Tempest connection and made Ariel a queer-coded man instead of a presumably straight woman he could’ve done something more interesting with the character.

In Clute’s introduction for Stations of the Tide he talks about authors being anchored in some time and place in their lives that their fiction tends to allude to, explicitly or implicitly. For Stephen King it’s always Maine circa 1960. For John Varley it’s always California between 1967 and 1975. For Delany it’s always Greenwich Village in the latter half of the ‘60s. This time-and-place-as-state-of-mind would overwhelm him when it came to Dhalgren and Trouble on Triton, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence these novels are not as genuinely SFnal as Babel-17 or Nova, or “Driftglass” over here. Delany at his best is like Swanwick at his best in that he’s able to give us glimpses into futures we can barely understand, and which he also probably struggles to understand for longer than controlled bursts. But he makes it look easy.

Kris

Reading Driftglass, I cannot help but think about magical realism. It was during the 60s that Borges work was being translated into English and I wonder if there is something to his setting it in South America is meant to evoking it. Not that I would classify this as within that genre but I feel like some lessons from it are coming out, with the casual elements of the fantastical, the invoking of Shakespeare and the kind of dream-like atmosphere.

Whilst I wouldn’t put it as my favourite Delany but what he does is always interesting. Here it is kind of hard to describe why I like it so much, it is more that it feels so unlike what anyone else was doing at the time. It is just so unusual and that is something in itself.