Aha, I recognise the source material for The Thing. I’ve only seen the recent remake film.This story is the most recognizable of the bunch, by plot if not by name. It struck me at the end that there were no women at all, not even a mention, though I suppose I should be glad because surely any depictions of women in SF from this era (strike the last three words) would be unfortunate. If I may make movie analogies, this and A Martian Oddysey both read closer to westerns than modern sci-fi. Maybe that’s just because they were written closer to the era westerns are set in than to today.

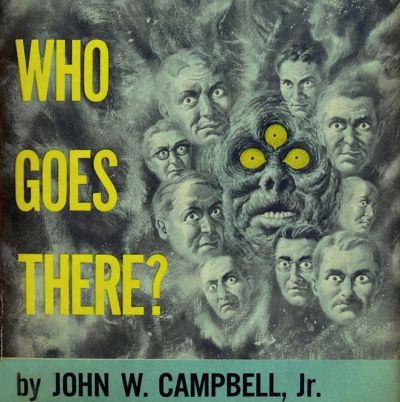

Who Goes There?

Don A. Stuart (John W. Campbell)

I picked Don A. Stuart’s 1938 novella Who Goes There? as the first story for Young People Read Old SF for two main reasons: the story is famous and the author is well-known for his other contributions to SF.

Don A. Stuart was the pen-name of John W. Campbell, Jr. He used the Stuart name for mood pieces and his own name for tales of star-smashing super-science. In 1937 Campbell became the editor of Astounding Science Fiction and, focused on editing, set his own writing career aside. He remained editor of Astounding (now called Analog) until his death in 1971. For betterand for worse, he was an influential figure in science fiction, as we might guess from the fact that not one but two awards are named after him. SF critics and historians sometimes divide SF into pre- and post-Campbell eras. Actually, Campbell spanned both these periods; later Campbell was in many ways a reaction to early Campbell. There’s a certain perverse fitness, then, to choosing one of Campbell’s own stories as an example of pre-Campbellian SF.

While readers may not have heard of Don A. Stuart or Who Goes There? , the odds are pretty good that they will have encountered one of its film adaptations, whether the 1951The Thing from Another World, 1982’s The Thing or the 2011 prequel, also called The Thing. Because, why mess with a good Thing?

If I’ve learned anything from the past two stories I’ve read, it’s not to fight the story, and let the story come to you. One of the strengths of Who Goes There is that the “type” of story I felt like I was reading changed 3 or 4 times as I continued to read. Right at the start, the story felt like an exploration story– a crew that had come across an abandoned camp, and were going to try to figure out what had happened (and who had gone) there. My initial assumption about the story was soon-to-be-disproved during Commander Garry’s initial narration. The commander provides a lay of the land, establishing that the crew is at the south pole and that there are two camps. He also introduced the actual plot device in the story: the ice-encased alien.

The alien’s introduction starts a debate about what to do – leave the alien encased in ice, or thaw it out? There is (allegedly) much that can be learned from thawing the alien, but there are also potential risks. I enjoyed thinking about the ethics surrounding research and knowledge gain. Are there some things that are just better not to know? Eventually, the “thaw” side wins the argument (knowledge acquisition trumps risk), the alien is thawed, and promptly escapes. I then formed my second soon-to-be-disproved assumption about the story: that the rest of the story would involve the crew chasing the murderous alien through the many subterranean corridors in a remote, antarctic camp. Happily, that was not the case – the alien was quickly found and killed. I was pleased to see that the story could be told with minimal violence (which was my third soon-to-be-disproved assumption about the story).

Upon further study of the alien and its first victim (one of the sled dogs), the crew discovers that the alien procreates by assuming the form of its victim and imitating the victim perfectly. The crew now has two objectives: figure out how to differentiate between real people and aliens, and kill all the aliens. As a big fan of mysteries, I found that I could relate to the first objective. I also found myself wondering what the difference is between the alien-pretending-to-be-a-person and the person themselves. Is it possible that the aliens would just continue to live out a normal, human life? Would that make them content? Or would they actually destroy the human race? It’s probably best to kill everything though, just to be safe

I am not a usual science fiction reader, I prefer to read mysteries. One of my favourite parts of a murder mystery is looking for clues, and trying to figure out who is what. Because the concept of the monster was so foreign to me, I wasn’t able to do that during Who Goes There. However, there were plenty of things to think about, plenty of assumptions to be proven wrong, and plenty of atmosphere, even without a final Big Reveal to explain everything.

—Lisa

At first glance, I was struck by the style and formatting of Who Goes There? Since I have a background in English literature with a special interest in the 19th and early 20th century, the style seemed reminiscent of early speculative fiction I have read. In a good way, the description is wordy and yet vague enough to allow the reader’s imagination to fill in the blanks. Knowing that this story is from the 1930s, I expected this type of style that I otherwise would have considered frustrating from an author published in recent years. As well, the description is needed to establish the rules and logic behind a genre without well-established tropes.

In terms of readability, I’m curious to know if the author wrote with the two-column format in mind. As something that I’m not used to, I found it more difficult to retain all of the technical details at once.

Being used to sci-fi/fantasy and science fiction set in utopian or distant worlds, I was surprised by the prevalence of horror tropes. It was a nice change from the fictional technical jargon and instead to read a science fiction story based on what might have been possible in the near future for the scientists of the 1930s.

I found it fascinating that in the end what defeats the alien being is logic. The men win by purely using their minds and not a technical scientific innovation. I question whether this was an expression of reassurance that no matter the advances of technology, the human mind would reign supreme. If so, this thread seems to have continued throughout sci-fi into present day with anxiety around rogue AI and the human mind and spirit winning out in the end.

The anxiety around atomic power shown by the atomic device being built by the alien ‘other’ reminds me of the foreignness of nuclear power at the time.

Overall, the story didn’t quite appeal to me. Perhaps it’s because I’ve read and studied one too many arctic expedition stories. Or perhaps it’s because I found it difficult to keep track of and differentiate between the large cast of characters. On an intellectual level, the story was entertaining. But on an emotional level, I didn’t feel engaged with the action.

—Mel

It is probably possible to spend more words explaining that they found a spaceship, accidentally blew it up, and brought back a frozen alien than the characters in the story did, but the audience in the book and all its readers would likely have died of boredom by that point.

Only to discover that all the numbers and details we are given to explain the presence of the frozen alien have practically no impact on the plot.

I’ve never been much of a fan of hard SF. It’s great that the author wants to give me all the numbers and intricate details of how the science in the story works. I usually find that they detract more than help the story. I care about plot and characters, I don’t care if your science works out exactly, especially when that science is almost 80 years out of date.

In this particular story, my patience for all the details was further hampered by the characters coming to incredibly accurate conclusions about the alien with minimal evidence to back them up. Perhaps that was supposed to be explained away by the alien’s telepathy projecting its thoughts into others minds, but the story was a bit too ambiguous about the source of this incredibly accurate knowledge.

Despite all these things working against the story for me, once we got past the incredibly long explanation for how they’d acquired a frozen alien, I did actually enjoy it.

While obviously thawing the thing found in the ice is NEVER a good idea, the author did a good job keeping the reader guessing which characters were aliens or not. The test that ultimately succeeded made sense within the context of the story. There was time spent on the consequences, not only for the end of the world scenario, but also for the people involved in the story. While the characters were fairly interchangeable, they clearly grasped the severity of their situation, and the author paid attention to the emotional toll that it would have on them.

Nothing in this story felt groundbreaking, but it’s hard to tell now what was new and innovative at the time it was written. Despite the general outline of the plot feeling predictable, there were enough details to keep me guessing. I feel that it would have benefited from being significantly shorter; even when the plot finally got moving it still took an age for anything to happen. Overall, though, there is a decent story embedded in all those words.