CordwainerSmith was a pen-name for Paul Linebarger, author of the 1948 classic,PsychologicalWarfare.Linebarger, as one might suspect, had workedfor the Central Intelligence Agency (as did another author due forperusal in this series). Thanks to his father’s political activity,Smith had ties to central players in Chinese politics from a veryyoung age: his godfather was SunYat-sen ;he was friends with ChiangKai-shek .Smith’s science fiction was influenced by Chinese literature, whichgave his fiction a style unusual in the western SF of the time.

Smithis comparatively unknown today. He died young, when he was onlyfifty-three. That was more than half a century ago. His body of workis comparatively small; his science fiction fits into two volumes.The Cordwainer Smith RediscoveryAward, which “honors under-read science fiction and fantasy authors withthe intention of drawing renewed attention to the winners,” wasnamed for him

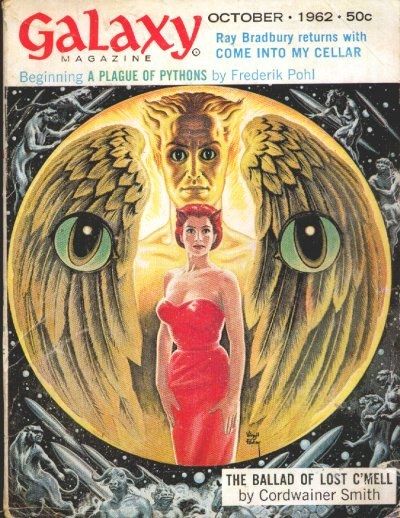

Smith’sbest known work is set several thousand years in the future, whenhumans have colonized the galaxy under the benevolent or at leastfirm hand of the Instrumentality. For humans, it’s a utopia. Forthe artificial Underpeople, created to serve humans and without anyrights at all, it is not. “The Ballad of Lost C’Mell” wasdeemed worthy of inclusion in TheScience Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume Two, whichhonored noteworthy stories denied a shot at the NebulaAward because they predated that award. How does it stand up in the eyes ofmy young readers?

TheRediscovery of Man: The Complete Short Science Fiction of CordwainerSmith available here.

Norstriliais availablehere.

This story did that thing where it is set so far in the future that anything is possible. If parts of the setting don’t quite make sense, it’s because humans achieved godlike power and immortality and then got bored with it and recreated a world like the old world but with whatever tweaks the author wants.

It was a very “white saviour” kind of story, where the suffering slaves needed one of the intelligent overlords to decide they needed saving. It was very condescending to C’Mell throughout. Even when complimenting her, it was couched in sexist (and I suppose racist?) terms.

The story was redeemed for me with the line “He had always been madly in love- with justice itself.” Just so over the top. I loved it. Made the rest of the story worth reading, and really brought Jestecost into focus as someone who really didn’t know what he was getting into, he was just a man child in love with the idea of justice. It made his other thoughts and actions make sense. As is often the case in stories like this, the decadent and all-powerful human race are childish in their desires and actions.

It reminded me of A World Out of Time which I found in a used book store in high school. Similar “so far in the future I can do whatever I want” setting. Similar treatment of female characters. I’m not sure why it is so hard to write women as actual people, but clearly a lot of authors struggle with it.

—Jamie

Stories like these are the reason why I don’t read science fiction. There are so many elements to sift through, they feel like window dressing or frivolous details designed to hide the fact that the plot is kind of bad and doesn’t really make sense.

My understanding of the plot is that a half-human-half-cat dies, his (super hot) daughter meets with the all-knowing leader who takes pity on the half-humans. The daughter falls in love with him after saying a few sentences to him, then acting as a telekinetic channel for the telekinetic half-human God. The leader and God (and daughter when she’s not acting as the telekinetic channel) come up with a plan to improve the lives of half-humans, who are not kindly looked upon. It involves showing the telekinetic god all their secrets which are stored in a giant magic 8 ball called The Bell. The plan works, the half-humans are allowed to become reserved grade citizens instead of half-slaves, which I think means they’re less uneven than before, but still not as good as regular-humans.

The super hot daughter becomes fat and old, and then she dies (but she has many super-hot daughters who go into the same line of 1960s era flight attendant/playboy bunny greeting work that their mother went into, but had to get out of when she became old and fat, even though their status in society has improved and by all accounts they shouldn’t have to go into those types of lines of work anymore). The all-knowing leader dies many years later, and on his deathbed the telekinetic God tells him that the super-hot daughter loved him.

The easiest part of the plot to understand is that the half-human daughter was super hot when she was young. Then she becomes old and fat. She was in love with the all-knowing guy, who knew everything except that the super-hot daughter was in love with him. What a wonderful story.

Maybe I just misunderstood the plot and it’s actually a good story! But to me it was pulpy, confusing, and full of out-dated ideas.

—Lisa

This story was much more a romance story of unrequited love than a sci-fi one. It opens and ends with a focus on the romance, although the middle is focused elsewhere.

Because the focus is on emotions and politics, the story ages quite well. And it helps that it’s set in a distant future, not a near one. There’s very little reference to specific technology or terms. Unlike other stories, this fits with the general tone of a story set in a world in which everyone receives telepathic brain scans at random: the less specific your thoughts and words, the better.

The only thing that seemed a bit dated was the drawing of the table of Lords, Lady and C’mell. The clothing and styles reminded me of a different time. Who wears a tux to work?

In general, it reminded me of The Minority Report or 1984 with its Bell system that can look through minds and cameras at superhuman speed. But on the whole, this story is original enough to stand on its own in my mind. The ending did remind me strongly of the meta-sentiment at the end of Shakespeare’s 18th sonnet (“So long lives this, and this gives life to thee”), and I think it’s to the story’s advantage that only one verse of the Ballad of Lost C’Mell is actually in the story. Much better to leave it to the reader’s imagination.

This story was very good, and intrigued me enough to look up more about it. The idea of animal-people and especially cat-people drew me in, so I could be biased in liking the story this much.

—Mel

I dislike this story a lot, and for several different reasons.

I found the narration style very frustrating. I found the constant reminders of the events in the future that the characters don’t know about annoying and they took me out of the story. Beyond that, the way that the narrator described and objectified C’Mell, constantly reminding us that she’s a “girly girl” or how her clothes are revealing kept reminding me that while the title implies that the story is supposedly about her, it is all through a distinctly male gaze.

I admit I was skeptical of this story before I even had really started it. There is two sentence introduction before the title which warned me that the story would be using romantic love as an inherently human characteristic. This story definitely uses that trope. Tying romantic love to humanity dehumanizes aromantic people, and relying on that idea is enough to make me dislike the story for that alone.

I didn’t feel like C’Mell got to be a real character. She was used as a tool, and there to be objectified and to fall in love with the guy. She even gets blamed when the clothes we are told are the only clothes she is allowed to wear are distracting. The only time we get to see how she feels or thinks is in relation to how she feels about him, and the events are more centred around how people use her than on what she could accomplish. We’re told she’s intelligent, but it seems she’s only remembered for falling in love.

I don’t like that this feels like a story that is focused on how wonderful it is that a member of the oppressive group decided that he should give marginalized people some rights. It’s great that the overall message is that giving oppressed people rights is a good thing, but I’d rather see stories centring the marginalized characters instead of praising allies for doing the bare minimum of recognizing that they’re people. Especially since this story seems to frame that as more of an ideological debate combined with fear of revolt, rather than him actually caring about the people involved.

Overall, I disliked this story for its style and its content. The insistence of romantic love as tied to humanity that was thrown in could have been easily avoided, and just makes me that much more frustrated.

—Mikayla