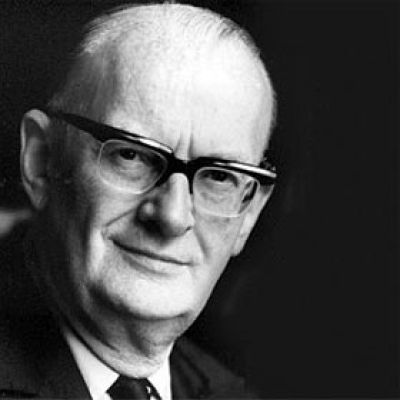

Arthur C. Clarke was once one of the Big Three of Science Fiction, up there with Asimov and Heinlein. In his day, he was known for both his fiction and his non-fiction, having carved out a niche as a pundit of note. His honours were diverse, including but not limited to the Hugo, the Academy Award, the Sri Lankabhimanya, and a CBE.

I knew I would be offering my subjects a Clarke story at some point, not because he is an old favourite of mine, but because Clarke was name-checked in the Facebook post that inspired Young People Read Old SF.

nobody discovers a lifelong love of science fiction through Asimov, Clarke, and Heinlein anymore, and directing newbies toward the work of those masters is a destructive thing, because the spark won’t happen.

But which Clarke? A White Hart anecdote? (No bar stories in this series … so far). A Meeting with Medusa? His creepy “A Walk in the Dark”? The puritanical “I Remember Babylon”? After considerable dithering, I selected 1951’s “Superiority,” because I thought pretty much everyone has had some worthy endeavour undermined by someone else’s desire to embrace a new shiny, whether it’s a committee member using email options they clearly have not mastered (1) or simply someone who discovers Windows 10 installing itself on their once useful computer. Or, in the case that inspired Clarke, the V2 rocket program that undermined the German war effort.

That logic made sense in my brain: does it stand up in the real world?

1: I am thinking specifically of the munged return address incident. I knew about the misleading error message issue with send mail, I just didn’t recognize it until I sent out a dozen duplicate emails. To many people. So many people.

How fitting for this footnote that I forgot that superscripting does not work on this site.

Now this story reads a lot closer to the modern SF I’ve read. The vocabulary and grammar are still a little archaic, but not nearly so much as the previous stories.

This is a story about really bad tacticians trying to blame scientists for their failures. How does anyone think unnecessarily retrofitting an entire fleet, all at once, in the middle of a war is a good idea? At most, take the excess ships that you have since you outnumber the other side and retrofit them first, then cycle them all out. This is all just very poor project management.

I have serious questions about the Exponential Field. How does a ship using one move when it’s turned on? Everything is infinitely far away from the ship so even at max speed it’ll get nowhere. To move you’d have to turn the field off, and then you’re back where you started. I suppose you could use it to lie in wait for the enemy, or to quickly disappear in the middle of a fight, but that isn’t how it’s described as being used. The side effects of the device were interesting, though they should have been caught in testing — something they apparently don’t do in this world.

The frivolous request of the narrator is indeed pretty frivolous. He doesn’t want to be housed with the scientist he thinks lost him the war? I

can’t imagine anyone wants to be housed with the admiral who *actually* lost the war.

—Jamie

“Superiority” reminded me of a company I used to work at. They made one pretty good software product. They decided to take advantage of new technology and try a bunch of things. None of the things really worked. Every team in the company blamed the other teams for the company’s failure, and the company ended up losing a bunch of money.

I’m not sure where elastic circle bands that stretch/distort the fabric of the universe fit into that story. But I guess there are elements of the story that still apply.

Maybe I read this story too quickly and without paying attention, but I found it about as captivating as the earliest stories we read, specifically Who Goes There and “Nightfall”. I’m also not sure what the point of the story is – that it’s better to keep trudging on doing the same old thing (if it works), rather than innovating? I guess that translates to something many 21st century workers can relate to – that software never ships on-time.

—Lisa

Hey look, it’s an author I’ve heard of! I have biases before reading this story: my memory tells me that Arthur C. Clarke is a classic intellectual author. I remember hearing that some like him, some don’t. Let’s see how this goes…

Has It Aged Well?

Technology-wise: no. Psychology-wise: yes.

I almost chuckled at the mention of a ship with “a million vacuum tubes”. Vacuum tubes seem quaint and outdated and even before my father’s time as an engineer.

Psychologically, the narrator blames one person for the defeat of the entire nation. The first Grand Admiral’s suicide echoes Hitler’s suicide, and the mentions of a court sounds a lot like the Nuremberg trials held in the years after the end of World War II. The impulse to blame people for failure and to punish people severely hasn’t gone away. We still threaten great violence and death on people based on a few actions. See: clickbait news articles and Twitter-shaming.

It Reminds Me Of…

No other media comes to mind specifically. The details of the story are general enough to be like any other future militaristic fiction. At the same time, there are enough specific names of planets and weapons to make a good story.

This story is a perfect example of opportunity costs. Relevant to today, since it’s possible to have many meaningless updates of technology. E.g. It seems that smartphones haven’t gotten better, just cheaper in the last few years. Better to stay with the apps I know than learning a new system that provides no more function.

Other Thoughts

The futuristic weapons describe the usual fears around nuclear weapons. This was the most cliché part. Otherwise, it seemed like a fairly original story to me. It definitely had a different angle — an unreliable narrator giving a legal testimonial.

Until a few paragraphs in, I wasn’t sure if this would be a story of unsuccessful invading aliens. Something like this. But nope.

Conclusion

The more I thought about it, the better the story seemed. I know a story is good when I immediately want to read it over again — I want to digest the words even more. I chew the cud to extract everything the story has to offer.

This makes me interested to read more Arthur C. Clarke stories.

—Mel

So a bunch of guys get overexcited about shiny new toys, made terrible decisions, refused to take any responsibility, and lost a war. One of them writes a long and boring letter explaining this situation in detail just to complain that he doesn’t want to live with the guy he’s blaming for everyone making terrible decisions.

End of story. There is literally nothing else here.

We don’t know why there’s a war, what it’s about, or why we should care who wins. We don’t get any character development from anyone. We don’t really get characters at all, just a bunch of mostly nameless random men.

Sure, we get lots of details about the specifics of the shiny toys that forced the obviously blameless military leaders to make terrible decisions. *eyeroll* We also get some whining about why the terrible decisions shouldn’t have been terrible ones, or at least were all the scientists fault for creating the shiny toys in the first place. But there aren’t any stakes, there’s nothing for the reader to care about.

I suppose that this could be a criticism of rapid technological progress and the abandoning of old technologies, but that ship has long since sailed. I’ve grown up in a world where technology has been rapidly changing my entire life. Clinging to old technology just because it’s old is as silly as ditching things that work just because there’s the promise of a new toy coming soon, and everyone should know by now that you never see theoretical performance in the real world.

The reveal at the end that the whole point of the letter is to complain about his roommate is just the final straw in how much I do not care. My reaction to the letter writer is to tell him to grow up, stop whining and take some responsibilities for his own mistakes. If I have to read a story that is entirely a guy whining about how life is unfair, there could as least be some attempt to make it interesting.

—Mikayla