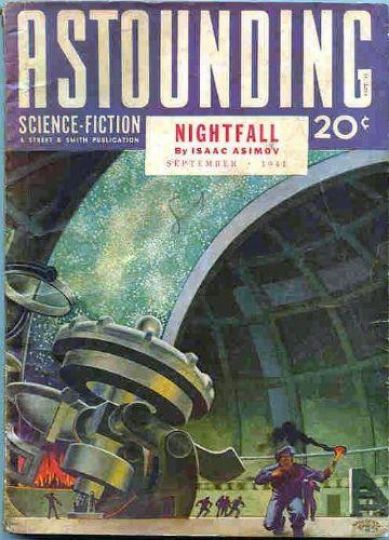

Isaac Asimov (1920 – 1992) was an extremely prolific (and popular) author of fiction and non-fiction. He was one of the authors name-checked in the essay that inspired my review series Young People Read Old SFF . So which of his short stories to choose? I admit to being torn between 1941’s “Nightfall” and 1952’s “The Martian Way”; both are well-known, both are deemed Hall-of-Fame-worthy. In the end, “Nightfall” won, because it seemed to be the more famous of the two stories, the only one to get a (somewhat regrettable) novel-length expansion and the only one of the two to get its own (very regrettable) movie. Two movies, in fact.

Asimov seems thus far to have been spared the erasure other once-prominent authors suffer after their death; Kitchener Public Library’s card catalog indicates 48 Asimov books lurk here and there in the stacks. Did the 21-year-old Asimov who wrote “Nightfall” have what it takes for his fiction to stay relevant seven decades later?

I’ve actually read this one before, in a collection of Asimov stories. I had forgotten the details but knew what the big reveal was. Maybe because I read and liked the Foundation stories I don’t find the prose in this story so foreign. And foreign is the word for all these stories. They were clearly written by people who lived in a different time and place. People just don’t speak like that anymore and writers don’t write dialogue like that anymore.

The format is one that I’ve seen in other stories, a journalist chasing a story as a means to give the scientists someone to explain to. It’s a good trick, and kept the story moving.

A couple questions nagged at me a while after reading this story. First I had to check in on the stability of a stellar system like the one described. The best I found was that it could be stable for a few years, but it’s very unlikely that it would be stable for more than one or two ‘cycles’ of 2500 years. The second question was about the society’s reaction to darkness. Did these people never close their eyes for long? Did they have no buildings more than one room deep? Thick walled tombs? Thick *blankets*? How is it that they have sophisticated telescopes but needed to invent the candle just a few weeks before the story? Were there no thrill-seeking spelunkers exploring caves using torches? You’d think that with a species-wide phobia of the dark they would be all over artificial light sources so that they never need to be in the dark even during bad weather.

—Jamie

This is my fourth attempt to write my impressions of the story. I have had a hard time writing something that:

- Doesn’t make me sound dumb.

- Doesn’t make me sound pretentious.

- Doesn’t make me sound dumb and pretentious.

So please enjoy my point-form impressions of Asimov’s Nightfall.

- This is the first story I’ve read that had distinct characters (i.e. Different characters who respond to the same stimulus differently.) I’d missed that in the first two stories, so it’s nice to see that.

- Asimov really hates religion.

- I liked the thought that people had never invented lamps because it never got dark.

- The story talked a lot and set up a universe that, as far as I could tell didn’t go very far.

Nightfall was a decent enough introduction to Asimov, as a person and as a writer. Would I read him again? Meh.

—Lisa

Before reading this story, I had absorbed the vague opinion that Asimov isn’t for everyone. Nightfall was less ‘Astounding Science Fiction’ and more ‘tediously detailed mind exercise’. Although free of glaring contradictions to current science – partly because the story took place on an imaginary planet – the narrative felt like an introduction leading up to the action that never happened.

I imagine the lack of fantastical ideas has to do with the timing of Nightfall’s publication, and demand for comforting stories. It’s a basic what-if scenario. Easy to grasp. Heck, Asimov even includes explanations of basic scientific principles just in case.

I imagine a teenager going to the shops. While running errands to check for mail from his older brother, he hears the radio blaring news and propaganda. Mother told him that once he bought the things on her list, he could have the extra quarter for himself. She won’t approve if he spends it all on candy. He spies the most recent issue of Astounding Science Fiction on the stand. Once he’s done reading it, he’s sure he can trade Jimmy for a different magazine. He buys it (plus one of the 5 cent candy bars). He gets home and reads the first story, chuckling at the silly men in the first story.

On the other hand, I have to admit that the writing style is excellent. It flowed easily without being overly technical, and there were no belaboured explanations of this alternative human culture. But I’m reminded of high school essays handed back with the comment: ‘Excellent writing. Work on developing your ideas.’

Conclusion: Good writing, but boring. Not for me.

-Mel

—Mel

When I was 15, my parents got us the I, Robot movie for Christmas. This prompted me to find the stories that had inspired the movie, only to discover that they were really rather boring and move on to read better things.

Turns out my opinion of Asimov has not improved in the last 12 years.

Eclipse as apocalypse is not exactly the most compelling apocalyptic story I’ve ever come across. I never bought that the eclipse was actually going to drive everyone insane, even as it was happening. The endless pages of talking about it only made me me thoroughly bored of the story. I never felt any tension, because I never believed them. Up until the very end I expected this story to be very anticlimactic, where life kept on going and everyone was fine.

I still think everything’s probably going to be fine. How long is the total eclipse going to last? A few hours? I don’t really think that that’s enough for the total collapse of civilization, although I suppose if everyone is really, truly, irrevocably insane, that might do it. (Is my scepticism showing?)

The whole premise of a society where nobody has ever been in the dark breaks my credulity too. Even with the number of suns this world has, nobody’s ever built a building with a windowless room in it? Nobody’s needed to invent a light source for any purpose? Or was it supposed to be the mere existence of stars that drove people insane? Because they kept going on and on (and on and on) about the darkness and claustrophobia, but our scientists had torches for light and they still went insane. There’s also the issue of who is likely to be able to survive this apocalypse. Classist much?

Going beyond the unlikeliness of the supposed apocalypse, all the characters in this story felt like stereotypes. The scientist that nobody believed until it was too late. The religious fanatic that believes science is blasphemy. The psychologist that’s there to explain at length why the world is doomed because of human nature. The reporter that’s there to give everyone somebody to talk to. None of the characters get any more development than that, because they aren’t characters, really. They’re props for Asimov’s thought experiment that’s pretending to be a story.

And of course, any women mentioned are far enough away that there’s no risk of them actually appearing in the narrative.

There are some ideas in the story that have potential. For example, there is mention of cooperation between the religious and scientific leaders that happened off screen. However, religion and science working together to improve knowledge would be far too interesting for this story, so we never get to actually see that happening.Unfortunately, there were far too few ideas that made me the slightest bit interested. I remain convinced of my prior opinion that Asimov’s work is boring and there are many better things I could spend my time reading.

—Mikayla