Stanley G. Weinbaum’s 1934 debut, “A Martian Odyssey,” is the second of the two short stories I have selected to represent the science fiction of the 1930s.

Weinbaum is one of the earliest hard SF writers, someone whose stories were shaped by what was then known (or guessed) of the other worlds of our solar system. .Weinbaum’s stories are little known and little read these days, in part because his career was so short: eighteen months from the publication of his first science fiction story to his death.

We may have forgotten Weinbaum, but his influence lingers. “A Martian Odyssey” was one of the first stories to try to imagine a truly alien alien. It was an inspiration to later writers.

“A Martian Odyssey” and other Stanley G. Weinbaum stories can be read for free here. As well, Leonaur has four Weinbaum collections, Interplanetary Odysseys, Other Earths,Strange Geniusand The Black Heart.

Right off the bat, I was immediately confused about where the characters were, why they were there, how to keep track of them, and what was unique about each of them. I spent more time than I probably should have reminding myself that Jarvis is the chemist, Putz is the engineer, Leroy is the biologist, and Harrison is the astronomer. In fact, I didn’t manage to get their personas straightened out at all when I first started reading. Eventually, I just gave up and read on, having faith that the continued narrative would straighten everything out for me. (It did– I should have let the story do the work for me instead of fighting it.)

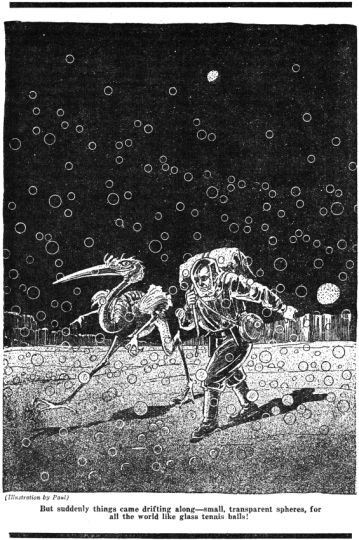

Once I let the story do the work for me, I started to enjoy Weinbaum’s creations. I was extremely impressed with the ability to flip the concept of life as I know it on its head – introducing us to Tweel, an intelligent life form that (probably) had a brain where humans would have a stomach, as well as a (presumably) silicon-based life form. All of these discoveries were filtered through the crew of the Ares, so we got a human interpretation of what was going on. I was also relieved that all of the questions I had while reading through the story were eventually answered. I even got a small glimpse into Jarvis and his life back on Earth, which tied into another fascinating and horrifying creature that he met on his journey. As a non-sci-fi reader, I’m not used to having faith that things will make sense later… things usually make sense right away, or at least take place in a world I understand. Weinbaum’s Mars is absolutely not something I understand, and I imagine this is something I’ll continue to find as I continue to read.

I also enjoyed the ending, which brought forth questions about whether we should continue to explore in spaces that are not rightfully ours, and how we should behave once we’re there. …leave it to the humans to be the biggest jerk interplanetary ambassadors around.

—Lisa

It’s the little things that bring you out of the story. Archaic units like gills, and watches that don’t tell you what day it is. Maybe even just people wearing watches.

This story seems a lot like making up a fantasy world and then making it SF by claiming it’s one of the planets in the solar system. Though this story spends more time fawning over the world building at the expense of plot than fantasy stories would be allowed. The setting is clearly the “old solar system” that I’ve heard about, before robotic exploration ruined everything for authors by showing what the planets were really like.

What quaint ideas about “atomic blasts” and the medicinal benefits of hard radiation. Writers of SF in the deep past were much more free to be optimistic about new scientific discoveries. Nowadays every new advance is going to cause at least as many problems as it solves, and the unexpected downsides are what drive the plots. This story is just happy to be exploring a crazy new planet and all it’s crazy improbable life forms, held down by only the lightest of plots. Old fashioned optimism about progress, I suppose.

—Jamie

From the start, this story was more interesting and in a more readable style than Who Goes There, even though both stories were published in the same decade. The story within a story structure meant it was full of dialogue, so I decided to read this one aloud. The dialogue reminded me of the early days of TV and radio when people had that peculiar cadence so that the audio recording would be crisp and clear.

This story is especially interesting now because of the real possibility of launching a few pioneering astronauts to Mars. Immediately, many of the details of Mars leapt out at me as amusing fictions, similar to the ridiculous Great Moon Hoax of 1835. (I learned about The Great Moon Hoax from 2 episodes of the excellent podcast Stuff You Missed in History Class. Also, do a google image search of “Great Moon Hoax”. It’s a cross between Wizard of Oz and early paintings of The New World.)

The story began with a thin (but breathable) atmosphere and plant-animals, so my brain immediately put this in the category of ‘alternate reality’. Today, pop science publications would be over the moon to discover such definitive proof of life on Mars.

Some jarring points in the story:

- “I noticed a little black bag or case hung about the neck of the bird-thing! It was intelligent! That or tame, I assumed.” – Why would you assume this creature is intelligent first, and tame second? Maybe it’s wishful thinking on the character’s part since it turns out the creature is intelligent.

- “Better than zippers.” –This seemed dated and made me wonder how long it took for zippers to catch on in real life.

- “I pointed to myself and then to the earth itself shining bright green…” — Brain: No. Wrong colour. Also, how close are Earth and Mars to each other in this story?

- “the Negritoes, for instance, who haven’t any generic words…They’re too primitive to understand that rain water and sea water are just different aspects of the same thing.” –Ouch.

The ending with the barrel creatures triggered a distant memory of randomly reading The Time Machine as a tween.

Overall, I quite liked this story. Whenever I finish a story and immediately go back to read bits of it again, I know it’s a good story.

8.5÷10

-Mel

—Mel

I have absolutely no idea what the general level of scientific understanding was of Mars in the 1930s, but for me this story was so much beyond my ability to suspend disbelief. The idea of sentient beings, significant vegetation, or a breathable atmosphere on Mars just doesn’t work for me. And even if I pretend this is some other planet, I can’t accept the idea that we wouldn’t have noticed all the things the narrator found long before people got there. I mean, just look at the pictures we’re getting back from Pluto!

I can see how this was trying to parallel the Odyssey, but the pacing bothered me. I felt like I often do watching old TV. Please, just get on with the story already. Probably partially due to my suspense of disbelief being thoroughly shattered, I just wanted him to get to the point of his story. The magical radiation medical machine wasn’t really worth the wait.

Speaking of radiation, the characters in this story were entirely too comfortable using “atomic blasts” to get around on this apparently living world. I wouldn’t want to be them, or anyone underneath their vehicles.

The casual racism in this was disappointing, but not particularly unexpected. Our narrator could cope with the idea of an intelligent other species that could think of things in different ways, but if it is a different human culture, of course that’s a sign that they’re terribly primitive and not up to civilized standards. [eye roll]

Despite the time since this was written, the all male crew and their attitudes still rings true today, if my experience on industrial sites is any indication.

I noticed the wording used in the story much more than I usually do. I found some of the language and descriptions to be ……different from what I’d expect today. Phrases like “stared sympathetically” and “blinked attentively” just seemed odd, while using the word “ejaculated” to describe someone speaking with excitement is really unfortunate.

Overall, I found this story slow, and I never really bought into the premise. Any tension that might have been there is diffused since the narrator obviously lived so he could tell this story to us.

—Mikayla